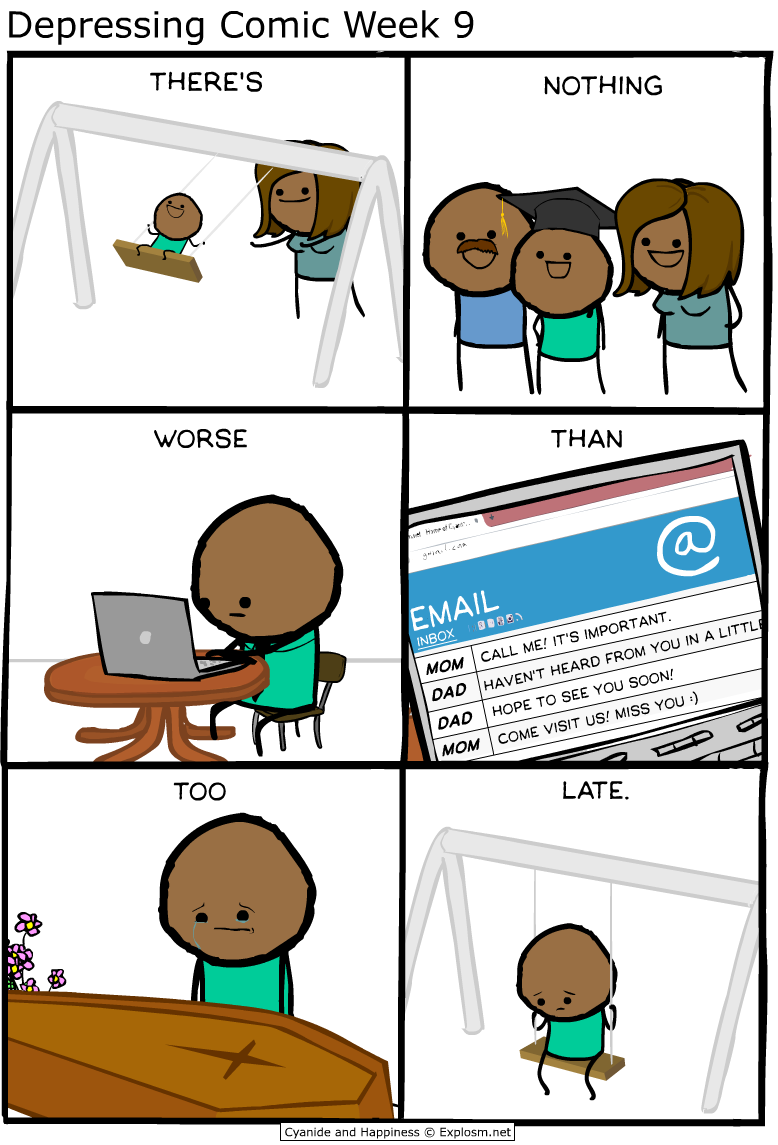

Yeah, that's about right.

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

Saturday, July 4, 2015

The first decade

Ten years ago today I received a phone call from my mum. She told me that my brother Dylan, had killed himself. Here's what I wrote in my journal the following day:

My brother committed suicide on Friday. It hasn't sunk in yet, and all family and friends are being really good about it. I've never lost anyone close before and I don't know how bad things will get or how long it will take to get through it, but the next couple of months are going to be difficult. It seems very odd that a week ago there were four or us and now there are only three of us.

Finding a meaningful sense of time was important. As you can see from the quote above, at first I was thinking about a few weeks or months at a time. As things got worse it would be days at a time. Since this was such a huge change in my life I'd occasionally think about years, or even decades at a time. I always told myself that the first decade would be the hardest. I'm in my early 30s, and if I'm lucky I've got another five decades left in me. Looking back at what I've done and where I've been in that time it's been an excellent decade, all things considered. I moved abroad to give myself time and space to come to terms with the loss. That was a long time ago, and for the past few months I've been thinking about moving back to the UK and getting back to "normal", whatever that means. Losing Moritz three months ago sped up that process quite a lot.

After ten years I've moved on from the loss and found new motivations in my life. Occasionally I still wake up thinking that Dylan is still alive, and that I'll see him again. Old memories of Dylan still resurface from time to time. Every now and then I remember that 40 years from now it will just be me and my two sisters, and one of the closest people I thought would always be there for me is gone forever.

The first decade without Dylan has passed. Losing him was hard. Losing him to suicide made it even harder. The experience has left me more resilient, more daring, and more outgoing, but at the same time it has left me a bit colder than before in some respects. I've always preferred deep friendships over relationships, and losing Dylan reinforced that feeling. I just don't feel comfortable being that close to someone. Seeing parent divorce, then Dylan choosing to die, moving country every few years, and brilliant friends coming and going for over a decade has left me with the impression that nothing is permanent or secure. Looking far in the future can be scary. Losing Dylan has changed me forever and feels as though I've had a shadow cast over some of the best years of my life. Even so I've managed to have a lot of fun and I like to think that Dylan would be happy to see me now and proud of what I've achieved. He would have loved to visit me in California or Geneva or Brussels, but he chose not to. He decided that whatever future lay ahead of him wasn't worth having. If the next decade is the same as the last in terms of opportunities, friendships, work, and travel, then that's definitely something I want to be a part of. I've rebuilt my life, and I'm just getting started. Today's a tough day, but that just gives me more strength to go on.

Monday, May 4, 2015

Moritz's funeral

It's been over a week since Moritz's funeral and I've had very mixed feelings (and not much time to blog about them) ever since. The day itself was very intense, and the days after were also very rough. Rather than rewrite what I've already written I thought I'd share some things that's I've written to some friends before and since the funeral. On the day itself I had intended to talk about Moritz and had prepared some text to read out. However in the end I didn't speak up for a few reasons. First of all much of what I wanted to say had already been said and I didn't want to talk for the sake of talking. The second reason was that being at the funeral brought up some very difficult feelings about Dylan, so it feel completely "safe" (or completely polite) to talk about my feelings. Thirdly I'd already sent a message which had been shared publicly, so I had already said something. Finally, while going over all this in my head, I hesitated too long and missed the opportunity. I'm still in two minds about whether I did the right thing in staying quiet. Here is what I had planned to say:

I first met Moritz in California. It was a bright, sunny day, and we were walking back from the main control room of the BaBar experiment. Moritz is the only person I've ever met whose eyes would actually light up, especially when the sun was shining. However it was only when we were both at CERN together that we became very close. My older brother died very suddenly and if was alive today he would be about Moritz's age. I think this is why we got along so well.

As soon as Moritz arrived in Geneva he started making friends and joining in activities wherever he could. From DVD nights, to hiking in the Jura, to evenings in Geneva and cocktail parties in Saint Genis, Moritz was always very sociable and always brought a lot of joy into the room. Life at CERN can be tough- the work is hard and people come and go so quickly. When you find a good friend it can make a huge difference, and you will often be lifelong friends. I thought with Moritz I would have a friendship that would last decades. He was more than just a friend to me, he was an ally, he'd tease me with jokes and make fun of how seriously we take things in Geneva. We would go to the gym together and afterwards sit in the sauna, talking about life, and work, and our hopes for the future, until it got too hot for me and I had to leave. We'd go out to bars with groups of friends in Geneva and since I organised the evenings I'd spend most of the night introducing people, making them feel welcome. When this got too tiring I'd sneak outside with Moritz to smoke a cigarette. I don't normally smoke, and in fact this was the only time I ever smoked a cigarette. But it gave me a chance to spend some time with Moritz, an old ally from our student days, in another foreign and strange country.

But Moritz was also spontaneous and I think that's what I will miss the most. I remember one time I saw him at the end of the day when I was working late, about to go home. Instead he caught my eye and asked me if I'd like to join him and a friend for some whiskey tasting. That simple and spontaneous act of generosity brightened up my day, and that wasn't the only time. Another time he asked if I wanted to hike up the reculet in the Jura mountains with him. A few hours later we were at the top, overlooking the Geneva valley in all its glory on one side and the sunset on the other. He took me away from the chaos of the lab and showed me how much natural beauty there was just waiting to be discovered, because he loved the outdoors so much.

Although Moritz had a short life, he had a very full life. In 35 years he managed to achieve more than most of us will ever achieve. He had travelled the world, taken part in the world class research, he made friends wherever he went and of course he loved to climb, and to make the most of everything around him. He had a brilliant sense of humour and could find the fun in anything. At one point one of the CERN experiments made its data public, so I decided to analyse it and put the results online to show people what could be done. Whenever we do this there's always a fear that someone inexperienced but optimistic will make a simple mistake and think that they have found a new particle that hundreds of scientists somehow missed. It was only a few hours before Moritz had taken my results and edited them to put add a false peak discovery in the data, and put it on facebook saying "Hobby researchers already found a strong unexpected signal!" I would have been angry, except it was very funny and at that point I was living in Brussels and already missing Moritz.

Earlier I said that he took part in world class research, but that's not quite true. He lead world class research, and only last month his work was presented at the very prestigious Moriond conference. It was Moritz's insight that lead to an important breakthrough, and without him there's no way to know how long it would take to make that step. His loss to the physics community is huge and will be felt for a very long time. He wasn't just a leader in research, he also lead in teaching. He took part in Master Classes, where the students' responses were overwhelmingly positive. He spoke with people both inside and outside of physics, of all ages. Many colleagues and friends have told me how much they enjoyed chatting with Moritz over beer or coffee [and as we have heard from Marco, his conversations inspired others]. The path to becoming a physicist is a long and difficult one, and it is through these kinds of conversations that inspire people and give them the courage to continue. Moritz may be gone, but his legacy will live on for many years. Decades from now there will be physicists who still will remember his kind words and sense of humour as the moment when they realised that they could follow the same path. They won't even know that he has passed away, and they will carry on the work he started.

I think that although Moritz died so young, there is some comfort that he enjoyed his life so much. His career was very successful. He was loved by many people all over the world. He loved his work and he loved his hobbies. From the time I met him to his final day he loved life and every day celebrated it with those around him. And for that I'm very grateful. I'll never forget him, and even though I miss him deeply, I am also very happy to have shared the time we had together.

I went to the funeral with a mutual friend, Marco. Not everyone could go to the funeral, so I wrote a summary of the day for a friend who could not make it. Here is what I told him:

Moritz's funeral was, as you would expect, a very intense experience. The service itself was entirely secular, lead by friends and family. People lit candles and left flowers at the church, there was guitar music and readings from friends and colleagues. We then went to the grave to bury the urn, then to a hotel for a reception. At the reception many people spoke about their memories of Moritz and there were many stories, photos and articles that people had shared. There were also copies of the LHCb document and some toys and school projects from his childhood. It was rather strange seeing these, because we don't often think about a person's childhood when you know them first as colleagues. People spoke about their memories (including Marco and Florian) and was very ambivalent about this, and in the end didn't speak up. I'd already shared some very personal reflections and felt that there was little I could add without repeating what had already been said.

After that Marco and I went to a restaurant and then drove back, but the rest of the physicists (about 12-15) went to a local bar and had beers in Moritz's memory. If we'd have known that was the plan we probably would have stayed another day in Trier. It was a very tough day for me and Marco. As well as losing Moritz, it brought back many painful memories of when my brother died and how hard the following years were.

The weekend after the funeral was spent mostly in my apartment feeling quite sad about everything. I had learned some more about the accident and it sounds like it was very fast and it was the result of Moritz either taking a risk or making a mistake, or both. That means right unti his final minutes he was very happy, and that nobody else has to feel any responsibility over the accident. That should have made me feel better, but I still very intensely sad about the loss, and a deep longing. I kept remembering him and imagining him laughing and joking. His family's words were "We are endlessly sad". I spent some time with some friends in Brussels to take my mind off things, and to talk about the future. That helped a lot, and right now I am in a much better place for it. I can see a bright future ahead of me, even if one my most talented and ambitious friends won't be there for it. There's no doubt in my mind that Moritz would have been an excellent professor, but as I tried to explain at the funeral (and probably did not succeed) I think I prefer to remember him young, brilliant, thirsty for more challenges and full of so much potential. I find that inspiring, motivating, and I'm going to use my memories of Moritz to push me to keep trying new things and keep moving forward with my life. The transition from a morose weekend after the funeral to where I am today (in the UK visiting old and new friends and planning out the next arc of my life) was not easy, but it was quite fast, and I'm grateful for that

Things are still a bit complicated by the grief over Dylan. The more I thought about how Moritz was happy right until the end the more I realised that Dylan wasn't. He was alone and afraid for a very long time. If he'd have contacted someone who could have stayed up with him all night and talked things over he could still be here now. For the first time in my life, after nearly a decade, I realised why my dad was so upset that he couldn't have helped Dylan. There's a fundamental difference between realising that nobody could help him (which was my own understanding at the time) and that a single pserson couldn't help him (which is how my dad felt, and then later on I felt.) The second feeling is one of immense pity, regret, and some sense of failure. By a large margin, that was the worst feeling I had at the funeral and that was the main reason I didn't stand up to speak. Marco did, and he was very brave to do so. I felt very proud to be with him when he spoke, and that compounded my own feelings of insecurity, as if I had failed Moritz and his family by not speaking up. Even so a safe space is a safe space, and I just didn't feel safe in that frame of mind.

Here are some rambling thoughts I sent to a friend on the matter:

I wanted to make sure that there was someone at the funeral who could talk about how much he'd be missed at CERN, but that was already said by someone else so I didn't feel so much of a need to say all this. I also didn't want to mess anything up- my feelings were very complicated that day, especially since I couldn't help comparing Moritz to Dylan and didn't want to end up saying anything inappropriate or insensitive. I think I made the right decision not speaking, but even so it feels like I failed in a way.

Dylan and I weren't very close towards the end, unfortunately. We didn't fall out or anything- he'd been living in Australia for a couple of years and returned to the UK 6 months before he killed himself. That was the final two terms of my final year as an undergrad at Oxford, and you know how hard I work, so as far as I can remember we didn't see each other face to face in that time. The last time I spoke to him was on the phone. I called my dad and Dylan picked up. I invited them both to visit me in Oxford when my exams were over and Dylan said he'd like that. A couple of weeks later he died and he never came to visit. It can't have been long after that phone call that he decided to kill himself. Obviously I'd have like to have seen him, and probably should have made more of an effort to see him in those 6 months, but I am glad that so close to the end he knew that I cared about him and wanted to see him again. I'm not sure how I'd have felt if I hadn't had that conversation with him. I think I still have quite a few emails from him that I never replied to, because I kept putting it off indefinitely.

To some extent I think that's why things were very hard with Moritz's death. I keep thinking to myself that I should have made more of an effort to spend time with him because I've always had the attitude that work is more important than keeping in touch with people, and that they'll always be there when I want to spend time with them. Obviously that's not the case, but we can't spend our lives trying to spend as much time with everyone as possible, we'd never get anything done. It's hard not have a lot of regrets, for both Dylan and Moritz. They both had short and brilliant lives, and with Moritz I could not think of a better way for him to have gone- he was happy right up to the last minute and died doing what he loved. It's much harder dealing with their deaths than those of older people. I lost three of my grandparents in the years following Dylan's death, and a very inspiring teacher a few years before, all after long periods of declining health. I was sad to lose them, but it was nowhere near as tough as it was with Dylan or Moritz.

Instead of focusing on how I should have spent more time with Moritz I'm trying to see it like this: One day he was alive and loving life, and the next he wasn't. For him there was very little pain or regret or fear. The next day we heard about the news and have to go on with our lives, so although we're sad for our own losses it's better to be happier for the life that Moritz had. Things are diferent for Dylan, as he chose to die and it was only when I became angry at him that I started to come to terms with his death and start to move on. After struggling to make sense of Moritz's death I finally had to confront Dylan's state of mind. He must have been very afraid for a very long time. He drank around a litre of vodka before he died, and wrote a note. He knew that his death woud have a terrible effect on everyone else (although he had no idea how much and for how long the aftermath would last.) If he'd reached out to just one person who could have stayed up talking to him all night he might not have chosen to die. Even then I probably would have rolled my eyes at how melodramatic he'd been. It's strange that dying makes us feel a way that almost dying never can. If Moritz had broken his back and had to spend the rest of life in a wheelchair I'd feel nowhere near as crushed as I have done, even though for him it would probably be a much greater loss. That puts a lot of things in perspective and helps clarify a lot of thoughts, although it doesn't really make me feel any better.

I've been through a lot in the past couple of weeks and it's helping a lot to write it all down, so thanks for giving me the impetus to do that. I got a group email today from Moirtz's family, and the only phot they used was one of mine. It's from a hike in the Reculét, Moritz looks very happy, and for once it didn't make me feel sad to see it again, instead I'm glad I could help his family in some very small way. So things are getting better.

There are still some more things I need to write down before I can move on. Moritz's absence on LHCb is still being felt quite keenly. Visits to see various friends have helped in many different ways and I should explain how. I started my career in particle physics because I lost Dylan and needed time alone to rebuild my life. I don't want to end my career in the field just because Moritz died. To have such a wonderful time of life bookended by tragedies would be terrible. I've got a lot of hope for the next years, so I need to find a way to make that change that doesn't feel as though my life is being dictated by how I react to losing people.

Saturday, April 18, 2015

Weekend trip

This week I'm coming back to the UK for three days to deal with the fallout from Moritz's death and how it relates to Dylan's death. The way things have turned out I'll be going back in time with a four (now five) pronged approach. First I'll spend time with Lee, who I don't think new Moritz, but was a pillar of support for me when I was at CERN. Then I'll spend time with Tom and Eugenia, who knew of Moritz of California, in his former glory days. Then I'll move on to Tim and Graham who were also out in California at the same time. Then on to Jamie and Debbie who helped me when I was in Oxford, and whom I have no problem being completely open and honest with. Finally there's a friend who's very recently found out about a loss, so we'll be spending the day together. It's going to be cathartic, and although it feels as though I'm most of the way to being okay again, there's always space for a bit more healing before coming back to the real world.

The first day is done and I've spent most of that time talking about the future. That's a very important part of grief. When you can think about the future with optimism then that's a good sign that you're healing .

The house of cards

Perhaps one of the worst feelings I've experienced in the past week is that nothing has changed. I felt the same as I had when I was first in California, that I had no plan for the future. I felt like everything had fallen away from me and that I was alone again, struggling to find my place, struggling to find the strength to care about anything. It felt as though nothing I had accomplished in the past decade had meant anything. It took me a long time to get to a point where I was happy, and confident, and where I loved life. That was the state I was in when I was at CERN, and when I was spending time with (among other people) Moritz. I felt all that evaporate as if everything I had done was just a house of cards I'd constructed to make myself feel better. If I end up alone, grieving, finding it hard to care or focus on anything the had I really gained anything in the past decade?

It turns out that I've gained a lot. Having been through a more intense and long lived bereavement I have all the experience and tools I need to get through this bereavement, no matter how much it reminds of my loss of Dylan. In the course of a week I seem to have gone through most of the main phases of grief already, and I'm now planning for the future again. I've almost accepted Moritz's death now, with only occasionally having to remind myself that he's gone. Acceptance is much more important than happiness.

Small details bring big comfort

When someone dies unexpectedly there's a tendency to want to know more information. When Dylan died my first question was "How?" When Moritz died I was in shock for the first few days, but as I found out more about the accident the shock became easier to handle. It wasn't just me, a mutual friend was also keen to find out more. What we know is that Moritz suffered a climbing accident, that the conditions were perfect and the equipment in good order. It took me a while to realise what this meant, which is that it was the result of human error. We also know he died on the scene, so it was probably fast. I still want to know more, but I don't think it would be appropriate or helpful to to do so. For days I've been imagining how the accident happened, and its immediate aftermath. Those are the kinds of thoughts I can't seem to turn off, but they're fading away as I come to accept what happened. Right now any small amount of information about Moritz helps. Talking about him in the past tense helps. Learning more about the accident helps. Anything that makes this seem more real helps.

Introverted grieving

The weekend following Moritz's death gave me a sobering reminder of just how much of an introvert I am. To avoid confusion I'll describe what I think an introvert is. An introvert is someone who feels emotionally tired after extended social interaction. (Okay, I'm just one person and this is my own experience. Other introverts may have different experiences, mileages may vary etc.) It's a purposefully vague description, but what I mean is that I can't relax when there are people constantly demanding my attention. I have to prepare myself for social interaction, which goes unnoticed most of the time. However when times are tough, or I'm tired from work I find that social interaction can make me very irritable. There have been occasions when I've stayed up until 3am simply to find time to myself.

For two days after hearing about Moritz's death I had to be the CMS Shift Leader for eight hours each day. This means taking responsibility for decisions made in the Control Room and working with four other shifters who usually need some level of "babysitting". At the same time I was receiving a barrage of condolence messages and offers of support. After each shift I did my best to escape and be alone. As I wrote this I was at the lab in Brussels and not in the office. Rather than interact with people and their seemingly inane topics (seminars don't matter to me this week) I was sitting under a tree in the sun, writing a blog post.

The problem is that if social interaction comes at some emotional cost then the social interaction has to be worth that cost, and when you're having a tough time it's hard to justify. On top of this there are many things people try to say or do that don't even help. Most people's responses to being told of a death are to fall over themselves trying to sound sorry, and offering help that won't actually help. When this happens it's hard not to think that the other person is doing it for their sake rather than yours, or that they think being polite is more important than being sincere. What is more helpful is to give the grieving person some space and control over how to approach things. When I'm grieving I pick and choose who I spend time with very carefully. Most people simply don't exercise (or have) the social skills that are needed. Among the best choices are the people who have been bereaved themselves. Other good choices are those people who don't feel constrained by social convention or don't rely on etiquette, because to be blunt a lot of the stuff you say when you're trying to cope with loss can sound a little crazy or even crass. What you need is someone who can listen to that and not get caught up trying to work out what a socially acceptable response is (because there isn't one.)